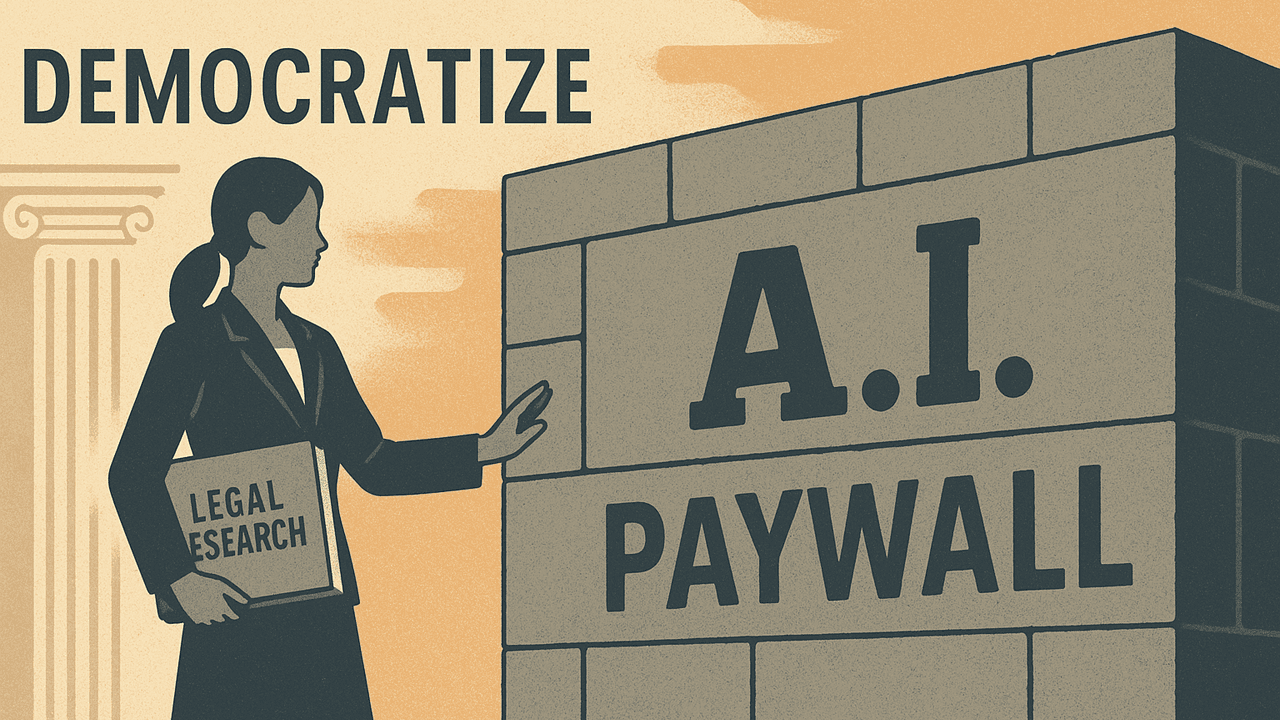

AI Was Supposed to Democratize Legal Research. What Happened?

For a brief, shining moment, it looked like AI might finally democratize legal research.

When I first started experimenting with LLMs like ChatGPT and tools like Casetext’s CoCounsel in 2023, I felt that exciting, slightly rebellious thrill:

_Finally, good legal analysis without a heavy price tag! _

It felt like legal tech was finally opening up, especially for those of us outside Big Law.

But that feeling is fading. And it's being replaced by something I'll call reluctant realism.

The Power of the Paywall

Even though court decisions are public, turning them into something searchable, tagged, and trustworthy is a massive undertaking — one LexisNexis and Westlaw have spent decades perfecting.

In my work advising attorneys on how to adopt and integrate AI into their practices, I’ve seen firsthand their excitement at the prospect of streamlining workflows and reducing their dependence on expensive research tools. But when we test low-cost general-purpose models like ChatGPT or Claude against niche legal issues, limits become obvious.

Westlaw and Lexis content isn’t just scraped from court dockets. It includes:

- Editorial headnotes.

- Shepard’s and KeyCite validation.

- Motion-tracking analytics .

- Cross-jurisdictional links.

- Enhanced with AI (thanks to partnerships with OpenAI (Lexis) and Microsoft (Thomson Reuters)).

These are not just search engines. They're fortified castles of legal knowledge, built brick by expensive brick over decades.

So while the core content might be "public," the value-added layers are very much private, and these companies price that value accordingly.

Casetext Closes the Door

When Thomson Reuters bought Casetext in 2023, many hoped it would stay open. By late 2024 it was folded into Westlaw Precision, and standalone access vanished. Citation reliability — one thing lawyers can’t compromise on — went back behind the paywall.

So now, LLMs like ChatGPT have :

- No access to Westlaw's live database.

- No access to Lexis' real content (even with their OpenAI partnership, it's for internal Lexis+ tools only).

- A dwindling supply of free, structured, open legal data to work with, presenting an ongoing challenge for effectively training AI for sophisticated legal research.

Is There Hope for Open Legal Research?

Projects like CourtListener, operated by the Free Law Project (FLP), are doing remarkable work by providing millions of legal opinions at no cost. FLP, a 501(c)(3), seeks to make the legal ecosystem more equitable and competitive. It operates without paywalls or venture backing, relying instead on grants and individual donations.

I regularly recommend CourtListener to the lawyers I advise, and I personally support its mission. Because its budget is lean, CourtListener delivers raw authenticity rather than editorial polish: you get the courts’ original PDFs, near real time ingestion, a free API, and a graph style citator, but not headnotes, negative treatment flags, or comprehensive secondary sources.

And vLex is emerging as an interesting middle-tier player with Vincent AI, offering AI-powered features and access to primary and secondary legal materials across more than 200 jurisdictions. It combines legal research, drafting tools, and multilingual capabilities in one platform — though still at a price ($399 a month for solos, and $230–270 a month per user for small firms).

But building the complex infrastructure to compete with Lexis or Westlaw is a monumental undertaking that open source initiatives cannot easily replicate. It demands significant financial investment, extensive time, and the dedicated effort of armies of legal editors, technologists and data scientists.

So here's the truth: the best legal research tools are going to remain expensive for the foreseeable future.

Do Lawyers Win or Lose?

That depends on which lawyer you ask.

If you work in Big Law, you’ve already got access to Westlaw or Lexis. Your firm is paying for the Cadillac package, and the new AI integrations will make your work even faster.

But you’re at a competitive disadvantage if you’re:

- A solo practitioner trying to stretch your research budget.

- A nonprofit legal clinic supporting tenants or domestic violence survivors.

- A small firm with tight margins.

And that’s what bothers me most.

Here's Where It Gets Interesting

But even if OpenAI or Anthropic were granted access to every paywalled legal database on Earth, another barrier remains: the inherently nuanced and interpreted nature of the law itself.

Legal reasoning isn’t always clean-cut. Some rules are elements-based (like contract formation or negligence), where checking all the boxes means you are likely to succeed. But others — especially in areas like copyright, family law, and constitutional law —a re factors-based, meaning a judge can weigh several considerations unevenly, with no clear formula.

Recently, I asked AI about the fair use defense to copyright law. It dutifully listed the four factors, but completely missed that in my jurisdiction, market impact outweighs the rest. Oftentimes nuance exists only in case law, sometimes buried in footnotes that only a seasoned lawyer would catch.

That level of interpretive legal reasoning remains one of AI’s most significant blind spots.

And because of the way LLMs are trained, hallucinations may never fully disappear. No matter how good the dataset is.

So Maybe This Is a Win for Lawyers?

It turns out lawyers aren’t going anywhere. At least not yet.

They still play a crucial role:

- Interpreting nuance.

- Applying sound, experienced legal judgment.

- Catching hallucinations before they appear in a filing or a court argument.

AI is an incredibly powerful tool. I use it daily to help attorneys rethink workflows, brainstorm more efficiently, and summarize complex documents. But it's not a substitute for legal reasoning. At least not today.

So yes, high-quality legal research is likely to remain expensive for the foreseeable future and out of reach for low-income practitioners.

Perhaps the ongoing tension between the potential for democratization and the necessity of accuracy is precisely where the next wave of legal innovation will emerge.

This friction, between the often deliberate and methodical pace of established institutions like government and the law, and the rapid and disruptive nature of the tech world, is where my reluctant realism regarding the future of truly democratized legal research takes root.

How can the legal tech world reconcile the need for rapid innovation with the inherent caution and rigor of the legal system? Let me know your thoughts.